|

David’s Island

Strategic Plot

Drawing made: 1996-97

Drawing size: 24” x 36”

Materials: Mylar, graphite,

ink, tape, found imagery, x-rays, foil, photographs, transfer letters +

trasnfer film, cut paper.

|

Drawing Architecture

A conversation with Perry Kulper

If “action painting” is produced by

the dynamics of dripping, smearing, and sweeping brushstrokes of paint to

reveal the complex character of abstract art, then “action drawing” would be

something like juxtaposing lines, planes, volumes, typographical elements,

photographs, and paper cutouts on a drawing that aims to uncover the

intricate universe of architectural ideas.

Each of Perry Kulper’s architectural

drawings is a cosmos of information and possibilities that resist the banal and

simplistic reductionism so typical of contemporary architectural

representation. Series after series, his drawings display objects as

background, and background as object in a constant visual journey of an

architecture that doesn’t settle and always evolves: an architecture of

ideas.

WAI discussed with Perry Kulper the concept, intention, and potential of

drawing architecture.

|

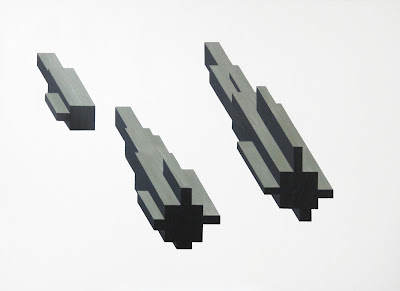

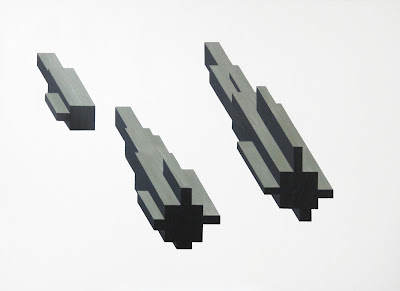

‘Fast Twitch’, Desert House

Site Plan v.01

Drawing made: 2004

Drawing size: 24” x 36”

Materials: Mylar, graphite,

tape, found imagery. transfer letters + transfer film, cut paper.

|

WAI: There was a moment in our academic

experience in which we became very interested in the potential of

representation strategy. This was at the same time as one

of us was researching about the potential of the representation tools of the

avant-garde in the 20th century, starting with Le Corbusier and

ending in the late 1960’s with projects by Archizoom and Superstudio.

Following our studies we discovered

in Europe, in the midst of the debacle of Wall Street, that the architectural

crisis had started a long time before the crash of Lehman Brothers.

We felt that architectural representation and its dialectical relationship with

architectural thinking was being overlooked, as representation was becoming a

mere sales exercise in which renderings and cartoonesque diagrams served as

smoke screens that tried to disguise a lack of intellectual

depth.

In order to continue our interests

and answering a strong urge to challenge the situation we created

WAI.

We would like to know about

the origins of your fascination for solving the puzzle of architectural

representation? Could you share with us how your interest in this realm of

architecture started?

Perry Kulper: While I had a latent interest in architectural drawings in

my time in grad school at Columbia (Archigram, Graves, Stirling, Abraham, etc)

and in the offices where I worked, my active interests in architectural

representation evolved through: a self reflection on my own limitations as a

designer through a realization that I lacked the formal, material and

representational skills to work on a fruitful range of ideas; an interest in

trying to find ways to visualize and materialize thought; trying to find a way

into unexplored disciplinary conversations; exposure to a range of architecture

and art practices in Los Angeles that opened questions about what architectural

representation might discuss.

My interests in architectural representation were

motivated specifically by my early years of teaching at SCI-Arc where I was

around a number of provocative people who were thinking and working on the

potential of the architectural drawing including Thom Mayne and Michael Rotondi

of Morphosis, Mary-Ann Ray and Robert Mangurian of Studio Works, Andy Zago,

Neil Denari, Coy Howard and so on. I was also beginning to think about the

preferences of various kinds of architectural drawings and I was formulating

thoughts about the ‘crisis of reduction’ and how the architectural

representation might help avoid the reduction of things too quickly in the

design of a project. I was also wondering how I might account for things that couldn’t be metrically, or instrumentally

visualized and was moving from my more dominant formal

predilections in design to relational thinking and how to structure various

interests in spatial settings. This suggested to me that alternative forms of

visualization, imaging and drawing might be more effective in relation to an

increased range of ideational and architectural possibilities.

|

‘Bleached Out’

Relational Drawing , v.02

Drawing made 2003

Drawing size 24” x 36”

Materials: Mylar, graphite,

tape, found imagery. transfer letters + trasnfer film, cut paper.

|

During that period of time have you seen

architectural representation in general undergo substantial

changes or has the essence remained the same although

with a different set of tools?

Digital culture has and will continue to have significant

impact on the roles that visualizations have played for the architect over the

last 15- 20 years. What can be worked on, who can work on it and the

translation of what’s being worked on have changed in contemporary life.

Collaborative logics, forms of spatial generation, construction logics (linked

to digital fabrication, in particular) have changed the roles, questions and

operational positions for architectural representation. Arguably, the latent

capacities and tacit knowledge gained through the making of a drawing have been

changed through the instrumental techniques linked to various digital

protocols. The changes are less dramatic in practice and perhaps more vivid

with un-built projects and speculative research. Architectural representation

has changed to include other forms of imaging and visualization ‘outside’ the

conventions of drawing practices, opening

alternative potential for what’s in play and what’s not in a project. In some

influential discussions there has been a shift from what architecture looks

like to how it behaves –a movement from the configuration and image dominance

to parametric and performance logics. We’ve also witnessed an increase in the

roles of the meditating visualizations, particularly the use of

diagramming. There are certain questions that remain the same and others

that will change. Key disciplinary discussions linked to a multitude of

cultural shifts will be of increased importance as they become

integrated in spatial production, particularly in relation to shifts in the augmented or changing roles of

architectural representation.

Has your perception and understanding of

architectural representation changed during your years of experience as a

thinker, educator and practitioner? Have you seen an evolution or any dramatic

change in your approach towards architectural representation?

Yes, my sense about the potential of architectural

representation has both changed and been enlarged astronomically. Several key

things come to mind including: an increasing interest on my part to augment the

picturing of architecture (as the dominant mode of recognizing the potential of

a project), to the generative roles of mediating drawings and their capacities

to consider a wide range of ideas simultaneously, I have

augmented imaging form or its

abstraction through visualizations connected to relational thinking. In

addition to what things look like I am particularly interested in: how they are

structured; the roles that representation have played in expanding what I think

is possible ideationally, conceptually and materially; a clearer understanding

of the capacities of various approaches to architectural representation and

when to deploy them relative to the different phases of a projects development;

the value of moving between certainties explored in the space of representation

and hunches, guesses and flat out shots in the dark; the latent potential of

the drawing in relation to its explicit intent; an ability to work on and

through temporally active conditions rather

than static appearances; and an expanded sense of what might be considered as

fodder for the architectural mill.

When you mention that the approximations,

hunches, and shots in the darks have hugely increased, does that imply that the process has become

more artistic in the sense of a programmatic freedom that allows you to explore

representation “as” an end in itself, instead of representation as a possible

building in the future?

Partially, as a result of allowing uncertainties

to enter drawings I have enjoyed freedom of many kinds. A more relaxed and

accommodating approach has allowed me to work ‘creatively’ (always a dangerous

word) in broadened ways by supporting expanded relational capacities in the

drawings to discuss things that might not otherwise be in play. I try to

visualize and support ideas long enough to see if they might be relevant to a

project in the long run. Increasingly, I am less judgmental about possible

ideas for a project, especially in the early phases of a project –about whether

everything in play is suitable for the piece of work. Depending on what I am

working on I often make drawings, or parts of drawings that are not targeted at

a synthetic building proposal, but are specific in their intent –studying

erasure as a possible representational and spatial activity, for example.

With the liberations I’ve granted myself come different

kinds of possibilities including an ability to make connections where I hadn’t

seen them, to open the range of ideas that might belong to a project and to

work on things that might not initially, or ever, make sense. Eventually, I

tend to look for a fitness between the situation in which I am working (the

situation might include a site, or sites and their respective histories,

physicality, futures, etc, the cultural and disciplinary questions at stake,

considerations of like projects in the world, my ambitions for the work, etc)

and whatever I might propose –a kind of measure of what is relevant, or

appropriate to discuss in a project.

Explored through certain kinds of drawing techniques, the

hunches and approximations allow me to see other possibilities- the drawings

and my understanding of the work frequently gets richer and talks about an

expanded set of constituencies, or possible participants, real, conceptualized

and as yet unimaginable. To be honest, I also simply need to support some

considerations through drawing in the only ways I can at the moment because in

the early phases of a project, in particular, I often don’t know how to resolve

the geometric and material articulation for ideas. By allowing the co-existence

of fairly certain ideas and hunches I relax a need to get it all right and

enable conversations to emerge through the visualizations, discovering the

project rather than attempting to prove it. If I had the skills to

‘convert’ the intellectual project into a geometric and material one

immediately, I might not make mediating visualizations. On the other hand, the

potential that emerges as a result of making drawings that try and move ideas

to formations enables a multitude of unforeseen and sometimes profitable

trajectories to enter a project. Ultimately, some of the drawing efforts have

been testing grounds to examine the appropriateness of ideas and where ideas

might come from.

On that same line,

do you think that architectural representation can or should be appreciated as

an art in itself, or should it always remain judged as a purely architectural exercise?

A great question- I’ve had a range of conversations with

friends, colleagues and students over the years about your question. I think

that architectural representation has a range of things it can discuss, both

internal and external to the discipline. I think we should position and support

a broad range of ways in which architectural representation works including its

capacity to work as a design accomplice, to enabling musings without known

outcomes, to speculating on alternative agendas for architecture (the roles of

so-called paper architecture, for example) to, as you’ve suggested, being

objects in the world with their own potential. I don’t think architectural

representation should always be judged solely as an architectural exercise,

absolutely not. From my perspective it’s useful to expose the roles

architectural representations play, when and how they might be deployed, how

they relate to other forms of architectural representation and how, if

appropriate, they might find their spatial translation. For my work, I’m interested in

finding appropriate modes of representation given the tasks at hand- the

situational fitness of things again. I also value decisions I make in the

drawings that are not linked to the situation in which I am working, but are

linked to the agency of the drawing with its own potential.

Has any

specific strategy or tool helped you to have a better

understanding of the potential of architectural representation or of

architecture as a discipline?

Amongst a range of things that have happened relative to

your question a handful of key things occur to me. These include: the potential

of composite architectural drawings, or visualizations- using multiple

representation languages simultaneously in the same drawing; strategic

plotting —plotting relations of agents, actions and settings, over and through

time; analogical thinking —thinking and working through likenesses with

things, events, conceptual structures, etc; and an expanded sense of the

potential of architecture through the use of diverse design methods. I’ve

indentified 14 of them and those means for producing work have allowed me to

work on a highly varied range of ideas in different situations.

|

‘Central California History Museum’

Longitudinal Section

Drawing made 2010

Drawing size 24” x 36”

Materials: Mylar, graphite, tape, found imagery. transfer letters + trasnfer film, cut paper.

|

Referring to something you wrote in the piece “The Labor

of Architectural Drawing” when discussing the risk of drawing as a

confrontation with the “conceptual daylight of the blank drawing surface”, we

can’t help but see an allegory

with one of Jose Saramago’s literary masterpieces about a city in which a

mysterious outbreak makes people go blind. The blindness in the story is not

portrayed as the typical visual blackout, but on the contrary, it is manifested

as an incessant light that drowns the sight of those affected in an ocean of

milk in which any discernible contrast between the sky and the water has become

imperceptible.

In the story, the hero is portrayed as somebody whose

sense of duty and hope keeps her from going blind. In her struggle between her

feeling of impotence in front of the overwhelming amount of problems of a blind

society she has to carry the unbearable weight of responsibility and somehow

guilt of being the only one able to see.

When you affirm that architectural drawing’s “potential

for creative engagement with diverse ideas in a project are on the wane,” do

you feel as if architecture has lost

its sight, and that there are just a few architects able to

see and understand the potential of architectural representation as a tool to

think architecture?

The Saramago (‘Blindness’, if my thin memory serves)

reference is interesting and useful, but I don’t think I am in a parallel world

to the hero. I think I’m looking for potential in architectural representation

that maybe others aren’t, but I also don’t expect them to

—the cultural and disciplinary questions and interests are just different. I do

see the world of architectural representation as amazingly well poised to act

as cultural and spatial agents, especially in the midst of significant change –as

a generative realm, not simply a descriptive medium, or a technique motivated

position.

I think there are multiple sights, or sites for the

discipline to work on. I don’t think architecture has lost its sight, it’s just

seeing other potentially interesting things at the moment. To be honest (this

is pure conjecture) I’m not sure there’s a broad interest in architectural

representation, or more specifically the roles of the architectural drawing at

the moment. In the early 21 Century architectural representation seems often to

be used instrumentally, often bypassing the expansive potential of

representation as a way to think through spatial problems and to enlarge what

it is that architecture might discuss.

Parenthetically, related to my interests in situational

thinking, in diversifying my skills as a designer and in trying to come to

terms with what kinds of issues are relevant to work on in a project (its

‘scope’ towards a cultural and disciplinary ‘fitness’) and how to work on them

(using particular design methods and representation techniques, strategically),

I am often interested in sustaining multiple families of ideas, or interests in

a project. Given my predilections the potential of architectural representation

is huge on this front.

|

David’s Island

Proto Strategic

Plot, Details

Drawing

made: 1996-96

Drawing

Size: 9” x 12”

Materials: Mylar, graphite,

found imagery, transfer film, cut paper.

|

Do you see your architectural approach as a mode

of intellectual resistance?

No. The approach, ethically, structurally and

operationally that I champion might be entirely different from project to

project, or from speculation to speculation. I think some people see what I do

as a mode of resistance, but that’s not my intent. I consider my interests more

a form of augmentation and challenging default positions rather than a mode of

resistance. If there is intellectual resistance it has more to do with

challenging the mono-project, while avoiding the crisis of reduction and

in not taking the means and techniques we deploy in architectural production

for granted. I have a desire to develop spatial scenarios that participate at

several levels with multiple constituencies in a spatial proposition-

culturally, disciplinarily and situationally.

And finally, referring to what you call

the crisis of reduction, do you think that the current architectural scenario (disciplinary,

academic, professional) offers a fertile soil for the development of

new representation strategies,

or is a radical change needed?

From my point of view, and very generally, I think the use

of representational strategies is sometimes deployed instrumentally and that

anything outside that usage is seen as peripheral, or outside what the

discussion might be. Because of my frequent interest in trying to support and

develop multiple families of ideas in a project, single, or mono-

drawing approaches tend to be inadequate to the questions I ask. Said

differently, I don’t always have the skills to figure out how to sustain ideas

I’m working on in a project through conventional drawings like plan, section,

perspective and so on. Given my predilections these drawing types, while historically

extraordinary in their own right, implicate synthetic understandings of the

ideas of a project at the time of their use. Sadly, my understanding and

ability to make synthetic decisions is often not ‘in sync’ with the preferences

or allowances of traditional drawing types.

And while I rely a lot on the conventions of architectural

representation, in fact I grew up in architecture education and in practice

through them; I have tried to understand their biases and preferences, so that

I can deploy representation strategies more tactically, given what I’m working

on. Again, I generally look for an appropriate set of relationships between

what’s being worked on and how those things are being worked on. Said

differently, drawing types ask the ‘lions to jump to the same platforms at the

same time’ and my design skills and interests simply don’t work that way.

I think there is a reasonable range of representational

strategies available disciplinarily, professionally and academically. I do

think we might address the question about contextualizing the representational

strategies available, what they’ve led to and when they are more effectively

deployed as a way. I also think that it’s possible to innovate within what’s

known, by shifting the relational assemblies, or relational contours within a

representational approach. To be honest I do think that radical changes might

be necessary.

|

Spatial Blooms

Il Gesu Study 2

2009

Digital Print

Assisted by Justn Foyle

|

Perry

Kulper is an architect and associate professor of

architecture at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture +

Urban Planning. Prior to his arrival at the University of Michigan he was a

SCI-Arc faculty member for 16 years as well as in visiting positions at the

University of Pennsylvania and Arizona State University. Subsequent to his

studies at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo (BS Arch)

and Columbia University (M Arch) he worked in the offices of Eisenman/

Robertson, Robert A.M. Stern and Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown before moving

to Los Angeles. His interests include the roles of representation and design

methods in the production of architecture and in broadening the conceptual

range by which architecture contributes to our cultural imagination.